Many custom options...

And formats...

The name Courage to Change in Chinese / Japanese...

Buy a Courage to Change calligraphy wall scroll here!

Personalize your custom “Courage to Change” project by clicking the button next to your favorite “Courage to Change” title below...

1. Change

4. Move On / Change Way of Thinking

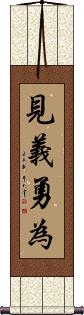

6. Courage to do what is right

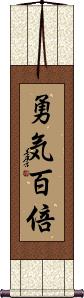

7. Inspire with redoubled courage

10. Honor Courage

11. Courage To Do What Is Right

12. Serenity Prayer

14. Serenity Prayer

17. Brave the Waves

18. Advance Bravely / Indomitable Spirit

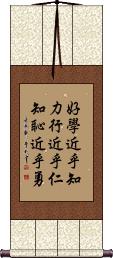

20. Learning leads to Knowledge, Study leads to Benevolence, Shame leads to Courage

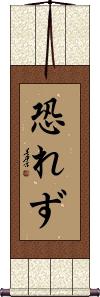

21. No Fear

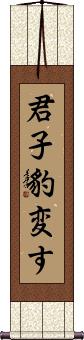

22. A Wise Man Changes His Mind

24. Mark the boat to find the lost sword / Ignoring the changing circumstances of the world

26. Zhong Kui

28. Sitting Quietly

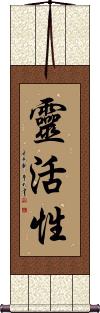

29. Flexibility

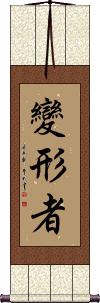

30. Shapeshifter

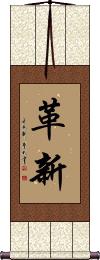

31. Innovation

33. No Surrender

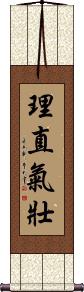

34. Dynamic

36. Joshua 1:9

37. Trust No One / Trust No Man

38. Lover / Spouse / Sweetheart

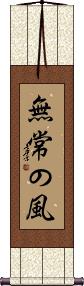

39. Mujo no Kaze / Wind of Impermanence

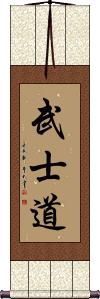

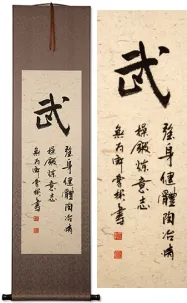

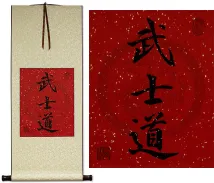

40. Bushido / The Way of the Samurai

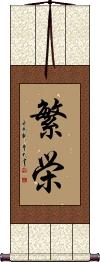

41. Prosperity

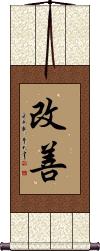

42. Kai Zen / Kaizen

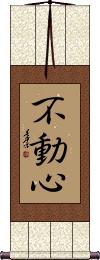

43. Immovable Mind

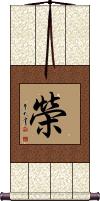

44. Glory and Honor

45. Islam

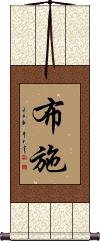

46. Dana: Almsgiving and Generosity

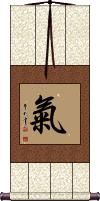

47. Life Energy / Spiritual Energy

49. England

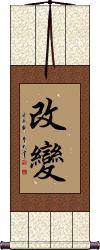

Change

改變 can mean to change, become different, or transform.

This can refer to the changing world or a person who changes their attitude or something about themselves.

![]() Note: An alternate version of the second character is used in Japanese. This is actually an old alternate Chinese form which is seldom seen in China anymore. If you want this version, please click on the Kanji shown to the right instead of the "Select and Customize" button.

Note: An alternate version of the second character is used in Japanese. This is actually an old alternate Chinese form which is seldom seen in China anymore. If you want this version, please click on the Kanji shown to the right instead of the "Select and Customize" button.

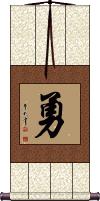

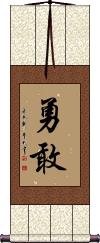

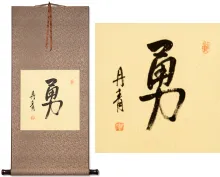

Bravery / Courage

Single Character for Courage

勇 can be translated as bravery, courage, valor, or fearless in Chinese, Japanese and Korean.

勇 is the simplest form to express courage or bravery, as there is also a two-character form that starts with this same character.

勇 can also be translated as brave, daring, fearless, plucky, or heroic.

This is also a virtue of the Samurai Warrior

See our page with just Code of the Samurai / Bushido here

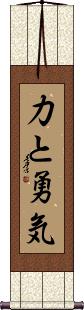

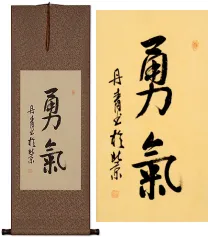

Bravery / Courage

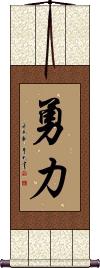

Courageous Energy

勇氣 is one of several ways to express bravery and courage in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean.

This version is the most spiritual. This is the essence of bravery from deep within your being. This is the mental state of being brave versus actual brave behavior. You'd more likely use this to say, “He is very courageous,” rather than “He fought courageously in the battle.”

The first character also means bravery or courage when it's seen alone. With the second character added, an element of energy or spirit is added. The second character is the same “chi” or “qi” energy that Kung Fu masters focus on when they strike. For this reason, you could say this means “spirit of courage” or “brave spirit.”

This is certainly a stronger word than just the first character alone.

Beyond bravery or courage, dictionaries also translate this word as valor/valour, nerve, audacity, daring, pluck, plucky, gallantry, guts, gutsy, and boldness.

This is also one of the 8 key concepts of tang soo do.

![]() While the version shown to the left is commonly used in Chinese and Korean Hanja (and ancient Japanese Kanji), please note that the second character is written with slightly fewer strokes in modern Japanese. If you want the modern Japanese version, please click on the character to the right. Both styles would be understood by native Chinese, Japanese, and many (but not all) Korean people. You should make your selection based on the intended audience for your calligraphy artwork. Or pick the single-character form of bravery/courage which is universal.

While the version shown to the left is commonly used in Chinese and Korean Hanja (and ancient Japanese Kanji), please note that the second character is written with slightly fewer strokes in modern Japanese. If you want the modern Japanese version, please click on the character to the right. Both styles would be understood by native Chinese, Japanese, and many (but not all) Korean people. You should make your selection based on the intended audience for your calligraphy artwork. Or pick the single-character form of bravery/courage which is universal.

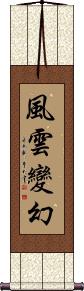

Wind of Change

風雲變幻 is a Chinese proverb that means “wind of change” or “changeable situation.”

The first character, 風, means wind, but when combined with the second character, 風雲, you have weather, winds and clouds, nature, or the elements. Colloquially, this can refer to an unstable situation or state of affairs.

The last two characters, 變幻, mean change or fluctuate.

Move On / Change Way of Thinking

乗り換える is the Japanese way to say “move on.” This can also be translated as “to change one's mind,” “to change methods,” or “to change one's way of thinking.” For instance, if you changed your love interest or political ideology, you might describe the act of that change with this title.

Colloquially in Japan, this is also used to describe the act of transferring trains or changing from one bus or train to another.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

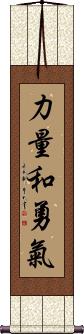

Courage and Strength

Courage to do what is right

見義勇為 means the courage to do what is right in Chinese.

This could also be translated as “Never hesitate to do what is right.”

This comes from Confucian thought:

Your courage should head in an honorable direction. For example, you should take action when the goal is to attain a just result as, without honorable intent, a person’s gutsy fervor can easily lead them astray.

One who flaunts courage but disregards justice is bound to do wrong; someone who possesses courage and morality is destined to become a hero.

Some text above paraphrased from The World of Chinese - The Character of 勇

See Also: Work Unselfishly for the Common Good | Justice | Bravery

Inspire with redoubled courage

Strength and Courage

Bravery / Courage

Courage in the face of Fear

勇敢 is about courage or bravery in the face of fear.

You do the right thing even when it is hard or scary. When you are courageous, you don't give up. You try new things. You admit mistakes. This kind of courage is the willingness to take action in the face of danger and peril.

勇敢 can also be translated as braveness, valor, heroic, fearless, boldness, prowess, gallantry, audacity, daring, dauntless, and/or courage in Japanese, Chinese, and Korean. This version of bravery/courage can be an adjective or a noun. The first character means bravery and courage by itself. The second character means “daring” by itself. The second character emphasizes the meaning of the first but adds the idea that you are not afraid of taking a dare, and you are not afraid of danger.

勇敢 is more about brave behavior and not so much the mental state of being brave. You'd more likely use this to say, “He fought courageously in the battle,” rather than “He is very courageous.”

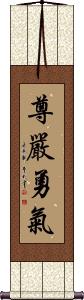

Honor Courage

尊嚴勇氣 is a word list that means “Honor [and] Courage.”

Word lists are not common in Chinese, but we've put this one in the best order/context to make it as natural as possible.

We used the “honor” that leans toward the definition of dignity and integrity since that seemed like the best match for courage.

Courage To Do What Is Right

義を見てせざるは勇なきなり is a Japanese proverb that means “Knowing what is right and not doing is a want of courage.”

I've also seen it translated as:

To see what is right, yet fail to do so, is a lack of courage.

To know righteousness, but take no action is cowardice.

You are a coward if you knew what was the right thing to do, but you did not take action.

Knowing what is right without practicing it betrays one's cowardice.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

Serenity Prayer

This is the serenity prayer, as used by many 12-step programs and support groups.

In Chinese, this says:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

Strength and Courage

Serenity Prayer

This is a Japanese version of the serenity prayer, as used by many 12-step programs and support groups.

In Japanese, this says:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

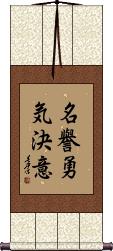

Honor Courage Commitment

Honor Courage Commitment

榮譽勇氣責任 is a word list that reads, “榮譽 勇氣 責任” or “honor courage commitment.”

If you are looking for this, it is likely that you are in the military (probably Navy or Marines).

We worked on this for a long time to find the right combination of words in Chinese. However, it should still be noted that word lists are not very natural in Chinese. Most of the time, there would be a subject, verb, and object for a phrase with this many words.

Fidelity Honor Courage

信義尊嚴勇氣 means fidelity, honor, and courage in Chinese.

This is a word list that was requested by a customer. Word lists are not common in Chinese, but we've put this one in the best order/context to make it as natural as possible.

We used the “honor” that leans toward the definition of “dignity” since that seemed the best match for the other two words.

Please note: These are three two-character words. You should choose the single-column format when you get to the options when you order this selection. The two-column option would split one word or be arranged with four characters on one side and two on the other.

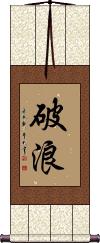

Brave the Waves

破浪 can be translated from Chinese as “braving the waves” or “bravely setting sail.”

It literally means: “break/cleave/cut [the] waves.”

破浪 is a great title to encourage yourself or someone else not to be afraid of problems or troubles.

Because of the context, this is especially good for sailors or yachtsmen and surfers too.

Note: While this can be understood in Japanese, it's not commonly used in Japan. Therefore, please consider this to be primarily a Chinese proverb.

Advance Bravely / Indomitable Spirit

This proverb creates an image of a warrior bravely advancing against an enemy regardless of the odds.

This proverb can also be translated as “indomitable spirit” or “march fearlessly onward.”

See Also: Indomitable | Fortitude

Fortune favors the brave

Learning leads to Knowledge, Study leads to Benevolence, Shame leads to Courage

No Fear

恐れず is probably the best way to express “No Fear” in Japanese.

The first Kanji and the following Hiragana character create a word that means: to fear, to be afraid of, frightened, or terrified.

The last Hiragana character serves to modify and negate the first word (put it in negative form). Basically, they carry a meaning like “without” or “keeping away.” 恐れず is almost like the English modifier “-less.”

Altogether, you get something like “Without Fear” or “Fearless.”

Here's an example of using this in a sentence: 彼女かのじょは思い切ったことを恐れずにやる。

Translation: She is not scared of taking big risks.

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

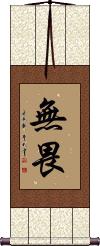

No Fear

(2 characters)

無畏 literally means “No Fear.” But perhaps not the most natural Chinese phrase (see our other “No Fear” phrase for a complete thought). However, this two-character version of “No Fear” seems to be a very popular way to translate this into Chinese when we checked Chinese Google.

Note: This also means “No Fear” in Japanese and Korean, but this character pair is not often used in Japan or Korea.

This term appears in various Chinese dictionaries with definitions like “without fear,” intrepidity, fearless, dauntless, and bold.

In the Buddhist context, this is a word derived from the word Abhaya, meaning: Fearless, dauntless, secure, nothing, and nobody to fear. Also, from vīra meaning: courageous, bold.

See Also: Never Give Up | No Worries | Undaunted | Bravery | Courage | Fear No Man

A Wise Man Changes His Mind (but a fool never will)

君子豹変す is a Japanese proverb that suggests that a wise man is willing to change his mind, but a fool will stubbornly never change his.

The first word is 君子 (kunshi), a man of virtue, a person of high rank, a wise man.

The second word is 豹変 (hyouhen), sudden change, complete change.

The last part, す (su), modifies the verb to a more humble form.

The “fool” part is merely implied or understood. So if wise and noble people are willing to change their minds, it automatically says that foolish people are unwilling to change.

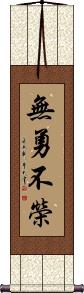

No Guts, No Glory

While difficult to translate “No guts no glory,” into Mandarin Chinese, 無勇不榮 is kind of close.

The first two characters mean “without bravery,” or “without courage.” In this case, bravery/courage is a stand-in for “guts.”

The last two characters mean “no glory.”

The idea that guts (internal organs) are somehow equal to courage, does not crossover to Chinese. However, translating the phrase back from Chinese to English, you get, “No Courage, No Glory,” which is pretty close to the intended idea.

Mark the boat to find the lost sword / Ignoring the changing circumstances of the world

刻舟求劍 is an originally-Chinese proverb that serves as a warning to people that things are always in a state of change.

Thus, you must consider that and not depend on the old ways or a way that may have worked in the past but is no longer valid.

This idiom/proverb comes from the following story:

A man was traveling in a ferry boat across a river. With him, he carried a treasured sword. Along the way, the man became overwhelmed and intoxicated by the beautiful view and accidentally dropped his prized sword into the river. Thinking quickly, he pulled out a knife and marked on the rail of the boat where exactly he had lost his sword.

When the boat arrived on the other side of the river, the man jumped out of the boat and searched for his sword right under where he'd made the mark. Of course, the boat had moved a great distance since he made the mark, and thus, he could not find the sword.

While this man may seem foolhardy, we must take a great lesson from this parable: Circumstances change, so one should use methods to handle the change. In modern China, this is used in business to mean that one should not depend on old business models for a changing market.

This proverb dates back to the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 BC) of the territory now known as China. It has spread and is somewhat known in Japan and Korea.

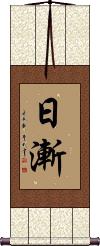

Progress Day by Day

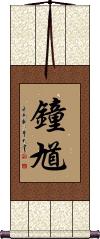

Zhong Kui

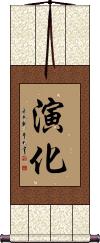

Evolve / Evolution

Sitting Quietly

Alone, this word means quite sitting, to sit quietly, or to meditate.

If you add and change the context a bit, this could mean to stage a sit-in (perhaps a non-violent protest by Buddhist monks or people). But again, as a single word as calligraphy art, it is the sitting quietly in meditation meaning that will be perceived.

Flexibility

靈活性 is a Chinese and Korean word that means flexibility or being open to change.

You consider others' ideas and feelings and don't insist on your own way. Flexibility gives you creative new ways to get things done. Flexibility helps you to keep changing for the better. 靈活性 could also be defined as having a “flexible nature.”

See Also: Cooperation

Shapeshifter

Innovation

革新 means innovate or innovation in Chinese, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja.

The literal meaning is “new leather,” but you must understand that colloquially, this leather character also means renewal, reform, change, or transformation.

While the first character is leather or reform, the second character strictly means “new.”

Engage with Confidence

理直氣壯 is a Chinese proverb that means “to do something while knowing you’re in the right.”

This can also be translated as and is appropriate when you are:

“In the right and self-confident”

“Bold and confident with justice on one's side”

“Having the courage of one's convictions”

“Justified and forceful”

“To be confident and vigorous because reason and logic are on one's side”

“Justified and confident”

No Surrender

Honor Does Not Allow Second Thoughts

義無反顧 is a Chinese proverb that can be translated in a few different ways. Here are some examples:

Honor does not allow one to glance back.

Duty-bound not to turn back.

No surrender.

To pursue justice with no second thoughts.

Never surrender your principles.

This proverb is about the courage to do what is right without questioning your decision to take the right and just course.

Dynamic

Moving / Motion / Ever-Changing

動 is the only Chinese/Japanese/Korean word that can encompass the idea of “dynamic” into one character.

動 can also mean:

to use; to act; to move; to change; motion; stir.

In the Buddhist context, it means: Movement arises from the nature of wind which is the cause of motion.

The key point of this word is that it represents motion or always moving. Some might say “lively” or certainly the opposite of something that is stagnant or dead.

Note: In Japanese, this can also be a female given name, Yurugi.

Justice / Righteousness

正義 means justice or righteousness in Chinese, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja.

Practicing justice and righteousness is being fair.

It solves problems, so everyone wins. You don't prejudge. You see people as individuals. You don't accept it when someone acts like a bully, cheats, or lies. Being a champion for justice takes courage. Sometimes when you stand for justice, you stand alone.

Note: This is also considered to be one of the Seven Heavenly Virtues.

Joshua 1:9

Here is the full translation of Joshua 1:9 into Chinese.

The text with punctuation:

我岂没有吩咐你吗?你当刚强壮胆。不要惧怕,也不要惊惶。因为你无论往哪里去,耶和华你的神必与你同在。

Hand-painted calligraphy does not retain punctuation.

This translation comes from the 1919 Chinese Union Bible.

For reference, from the KJV, this reads, “Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of a good courage; be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed: for the LORD thy God is with thee whithersoever thou goest.”

Trust No One / Trust No Man

誰も信じるな is as close as you can get to the phrase “trust no man” in Japanese, though no gender is specified.

The first two characters mean everyone or anyone but change to “no one” with the addition of a negative verb.

The third through fifth characters express the idea of believing in, placing trust in, confiding in, or having faith in.

The last character makes the sentence negative (without the last character, this would mean “trust everyone,” with that last character, it's “trust no one”).

Note: Because this selection contains some special Japanese Hiragana characters, it should be written by a Japanese calligrapher.

Lover / Spouse / Sweetheart

愛人 means lover, sweetheart, spouse, husband, wife, or beloved in Chinese, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja.

The first character means “love,” and the second means “person.”

This title can be used in many different ways, depending on the context. Husbands and wives may use this term for each other. But, if you change the context, this title could be used to mean “mistress.” It's pretty similar to the way we can use “lover” in many different ways in English.

In modern Japan, this lover title has slipped into the definition of mistress and is not good for a wall scroll.

Mujo no Kaze / Wind of Impermanence

無常の風 is an old Japanese proverb that means the wind of impermanence or the wind of change in Japanese.

This can refer to the force that ends life, like the wind scattering a flower's petals. Life is yet another impermanent existence that is fragile, blown out like a candle.

The first two characters mean uncertainty, transiency, impermanence, mutability, variable, and/or changeable.

In some Buddhist contexts, 無常 can be analogous to a spirit departing at death (with a suggestion of the impermanence of life).

The last two characters mean “of wind” or a possessive like “wind of...” but Japanese grammar will have the wind come last in the phrase.

Bushido / The Way of the Samurai

武士道 is the title for “The Code of the Samurai.”

Sometimes called “The Seven Virtues of the Samurai,” “The Bushido Code,” or “The Samurai Code of Chivalry.”

This would be read in Chinese characters, Japanese Kanji, and old Korean Hanja as “The Way of the Warrior,” “The Warrior's Way,” or “The Warrior's Code.”

It's a set of virtues that the Samurai of Japan and ancient warriors of China and Korea had to live and die by. However, while known throughout Asia, this title is mostly used in Japan and thought of as being of Japanese origin.

The seven commonly-accepted tenets or virtues of Bushido are Rectitude 義, Courage 勇, Benevolence 仁, Respect 礼(禮), Honour 名誉, Honesty 誠, and Loyalty 忠実. These tenets were part of oral history for generations, thus, you will see variations in the list of Bushido tenets depending on who you talk to.

See our page with just Code of the Samurai / Bushido here

Prosperity

繁栄 is the same “prosperity” as the Traditional Chinese version, except for a slight change in the way the second character is written (it's the Japanese Kanji deviation from the original/ancient Chinese form).

Chinese people will still be able to read this, though you should consider this to be the Japanese form (better if your audience is Japanese).

Sometimes, the Kanji form shown to the right is used in Japanese. It will depend on the calligrapher's mood as to which form you may receive. If you have a preference, please let us know at the time of your order.

Kai Zen / Kaizen

改善 means betterment, improvement, to make better, or to improve - specifically incremental and continuous improvement.

改善 became very important in post-war Japan when Edwards Deming came to Japan to teach concepts of incremental and continuous improvement (for which the big 3 auto-makers did not want to hear about at the time - even kicking Deming out of their offices). The Japanese workforce absorbed this concept when their culture was in flux and primed for change.

This kaizen term is closely associated with the western title “Total Quality Management.” Perhaps dear to my heart since I spent years studying this at university before I moved to China where TQM did not seem to exist. Slowly, this concept has entered China as well (I've actually given lectures on the subject in Beijing).

If you are trying to improve processes at your business or need to remind yourself of your continuous TQM goals, this would be a great wall scroll to hang behind your desk or in your workplace.

See Also: Kansei

Immovable Mind

fudoshin

不動心 is one of the five spirits of the warrior (budo) and is often used as a Japanese martial arts tenet.

Under that context, places such as the Budo Dojo define it this way: An unshakable mind and an immovable spirit is the state of fudoshin. It is courage and stability displayed both mentally and physically. Rather than indicating rigidity and inflexibility, fudoshin describes a condition that is not easily upset by internal thoughts or external forces. It is capable of receiving a strong attack while retaining composure and balance. It receives and yields lightly, grounds to the earth, and reflects aggression back to the source.

Other translations of this title include imperturbability, steadfastness, keeping a cool head in an emergency, or keeping one's calm (during a fight).

The first two Kanji alone mean immobility, firmness, fixed, steadfastness, motionless, and idle.

The last Kanji means heart, mind, soul, or essence.

Together, these three Kanji create a title defined as “immovable mind” within the context of Japanese martial arts. However, in Chinese, it would mean “motionless heart,” and in Korean Hanja, “wafting heart” or “floating heart.”

Glory and Honor

榮 relates to giving someone a tribute or praise.

It's a little odd as a gift, so this may not be the best selection for a wall scroll.

I've made this entry because this character is often misused as “honorable” or “keeping your honor.” It's not quite the same meaning, as this usually refers to a tribute or giving an honor to someone.

榮 is often found in tattoo books incorrectly listed as the western idea of personal honor or being honorable. Check with us before you get a tattoo that does not match the meaning you are really looking for. As a tattoo, this suggests that you either have a lot of pride in yourself or that you have a wish for prosperity for yourself and/or your family.

![]() In modern Japanese Kanji, glory and honor look like the image to the right.

In modern Japanese Kanji, glory and honor look like the image to the right.

There is a lot of confusion about this character, so here are some alternate translations for this character: prosperous, flourishing, blooming (like a flower), glorious beauty, proud, praise, rich, or it can be the family name “Rong.” The context in which the character is used can change the meaning between these various ideas.

In the old days, this could be an honor paid to someone by the Emperor (basically a designation by the Emperor that a person has high standing).

To sum it up: 榮 has a positive meaning; however, it's a different flavor than the idea of being honorable and having integrity.

Islam

(phonetic version)

伊斯蘭教 both means and sounds like “Islam” in Mandarin Chinese.

The first three characters sound like the word “Islam,” and the last character means “religion” or “teaching.” It's the most general term for “Islam” in China. The highest concentration of Muslims in China is Xinjiang (the vast region in northwest China that was called The East Turkistan Republic until 1949 and is sometimes called Chinese Turkistan, Uyghuristan). Here you will find Uygurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and others that are descendants of Turkmen (possibly mixed with Persians and Arabs). Many of their ancestors were traders who traveled the silk road to buy and sell spices and silk and exchange other goods from the Orient and the Middle East.

I spent some time in Xinjiang and got to know this community. They are strong people who can endure much. They are friendly and love to have a good time. I was a stranger but was treated by villagers (near China's border with Afghanistan) as if I was a good friend.

However, I have heard that it's best not to cross them, as in this land, the law is the blade, and everything is “eye for an eye.” The Chinese government has little control in Xinjiang, with almost no police officers except in the capital of Urumqi (so it's a 60-hour roundtrip train ride to seek the aid of law enforcement in most cases).

While few seem devout, there are at least small mosques in every village. And you will never see a man or woman outside without a head covering.

It should be noted that these people are all citizens of China, but they are officially of the Caucasian race. A visit to Xinjiang will change your idea of what it means to be Chinese.

Dana: Almsgiving and Generosity

布施 is the Buddhist practice of giving known as Dāna or दान from Pali and Sanskrit.

Depending on the context, this can be alms-giving, acts of charity, or offerings (usually money) to a priest for reading sutras or teachings.

Some will put Dāna in these two categories:

1. The pure or unsullied charity, which looks for no reward here but only in the hereafter.

2. The sullied almsgiving whose object is personal benefit.

The first kind is, of course, the kind that a liberated or enlightened person will pursue.

Others will put Dāna in these categories:

1. Worldly or material gifts.

2. Unworldly or spiritual gifts.

You can also separate Dāna into these three kinds:

1. 財布施 Goods such as money, food, or material items.

2. 法布施 Dharma, as an act to teach or bestow the Buddhist doctrine onto others.

3. 無畏布施 Courage, as an act of facing fear to save someone or when standing up for someone or standing up for righteousness.

The philosophies and categorization of Dāna will vary among various monks, temples, and sects of Buddhism.

Breaking down the characters separately:

布 (sometimes written 佈) means to spread out or announce, but also means cloth. In ancient times, cloth or robs were given to the Buddhist monks annually as a gift of alms - I need to do more research, but I believe there is a relationship here.

施 means to grant, to give, to bestow, to act, to carry out, and by itself can mean Dāna as a single character.

Dāna can also be expressed as 檀那 (pronounced “tán nà” in Mandarin and dan-na or だんな in Japanese). 檀那 is a transliteration of Dāna. However, it has colloquially come to mean some unsavory or unrelated things in Japanese. So, I think 布施 is better for calligraphy on your wall to remind you to practice Dāna daily (or whenever possible).

Life Energy / Spiritual Energy

Chi Energy: Essence of Life / Energy Flow

This 氣 energy flow is a fundamental concept of traditional Asian culture.

氣 is romanized as “Qi” or “Chi” in Chinese, “Gi” in Korean, and “Ki” in Japanese.

Chi is believed to be part of everything that exists, as in “life force” or “spiritual energy.” It is most often translated as “energy flow” or literally as “air” or “breath.” Some people will simply translate this as “spirit,” but you must consider the kind of spirit we're talking about. I think this is weighted more toward energy than spirit.

The character itself is a representation of steam (or breath) rising from rice. To clarify, the character for rice looks like this: ![]()

Steam was apparently seen as visual evidence of the release of “life energy” when this concept was first developed. The Qi / Chi / Ki character is still used in compound words to mean steam or vapor.

The etymology of this character is a bit complicated. It's suggested that the first form of this character from bronze script (about 2500 years ago) looked like these samples:

However, it was easy to confuse this with the character for the number three. So the rice radical was added by 221 B.C. (the exact time of this change is debated). This first version with the rice radical looks like this:

The idea of Qi / Chi / Ki is really a philosophical concept. It's often used to refer to the “flow” of metaphysical energy that sustains living beings. Yet there is much debate that has continued for thousands of years as to whether Qi / Chi / Ki is pure energy or consists partially or fully of matter.

You can also see the character for Qi / Chi / Ki in common compound words such as Tai Chi / Tai Qi, Aikido, Reiki, and Qi Gong / Chi Kung.

In the modern Japanese Kanji, the rice radical has been changed into two strokes that form an X.

![]() The original and traditional Chinese form is still understood in Japanese, but we can also offer that modern Kanji form in our custom calligraphy. If you want this Japanese Kanji, please click on the character to the right instead of the “Select and Customize” button above.

The original and traditional Chinese form is still understood in Japanese, but we can also offer that modern Kanji form in our custom calligraphy. If you want this Japanese Kanji, please click on the character to the right instead of the “Select and Customize” button above.

More language notes: This is pronounced like “chee” in Mandarin Chinese, and like “key” in Japanese.

This is also the same way to write this in Korean Hanja where it is Romanized as “gi” and pronounced like “gee” but with a real G-sound, not a J-sound.

Though Vietnamese no longer use Chinese characters in their daily language, this character is still widely known in Vietnam.

See Also: Energy | Life Force | Vitality | Life | Birth | Soul

Better Late Than Never

It's Never Too Late Too Mend

Long ago in what is now China, there were many kingdoms throughout the land. This time period is known as “The Warring States Period” by historians because these kingdoms often did not get along with each other.

Sometime around 279 B.C. the Kingdom of Chu was a large but not particularly powerful kingdom. Part of the reason it lacked power was the fact that the King was surrounded by “yes men” who told him only what he wanted to hear. Many of the King's court officials were corrupt and incompetent which did not help the situation.

The King was not blameless himself, as he started spending much of his time being entertained by his many concubines.

One of the King's ministers, Zhuang Xin, saw problems on the horizon for the Kingdom, and warned the King, “Your Majesty, you are surrounded by people who tell you what you want to hear. They tell you things to make you happy and cause you to ignore important state affairs. If this is allowed to continue, the Kingdom of Chu will surely perish, and fall into ruins.”

This enraged the King who scolded Zhuang Xin for insulting the country and accused him of trying to create resentment among the people. Zhuang Xin explained, “I dare not curse the Kingdom of Chu but I feel that we face great danger in the future because of the current situation.” The King was simply not impressed with Zhuang Xin's words.

Seeing the King's displeasure with him and the King's fondness for his court of corrupt officials, Zhuang Xin asked permission from the King that he may take leave of the Kingdom of Chu, and travel to the State of Zhao to live. The King agreed, and Zhuang Xin left the Kingdom of Chu, perhaps forever.

Five months later, troops from the neighboring Kingdom of Qin invaded Chu, taking a huge tract of land. The King of Chu went into exile, and it appeared that soon, the Kingdom of Chu would no longer exist.

The King of Chu remembered the words of Zhuang Xin and sent some of his men to find him. Immediately, Zhuang Xin returned to meet the King. The first question asked by the King was “What can I do now?”

Zhuang Xin told the King this story:

A shepherd woke one morning to find a sheep missing. Looking at the pen saw a hole in the fence where a wolf had come through to steal one of his sheep. His friends told him that he had best fix the hole at once. But the Shepherd thought since the sheep is already gone, there is no use fixing the hole.

The next morning, another sheep was missing. And the Shepherd realized that he must mend the fence at once. Zhuang Xin then went on to make suggestions about what could be done to reclaim the land lost to the Kingdom of Qin, and reclaim the former glory and integrity of the Kingdom of Chu.

The Chinese idiom shown above came from this reply from Zhuang Xin to the King of Chu almost 2,300 years ago.

It translates roughly into English as...

“Even if you have lost some sheep, it's never too late to mend the fence.”

This proverb, 亡羊补牢犹未为晚, is often used in modern China when suggesting in a hopeful way that someone change their ways, or fix something in their life. It might be used to suggest fixing a marriage, quitting smoking, or getting back on track after taking an unfortunate path in life among other things one might fix in their life.

I suppose in the same way that we might say, “Today is the first day of the rest of your life” in our western cultures to suggest that you can always start anew.

Note: This does have Korean pronunciation but is not a well-known proverb in Korean (only Koreans familiar with ancient Chinese history would know it). Best if your audience is Chinese.

England

Can mean: Courage / Bravery

In Chinese, Japanese, and old Korean, 英 can often be confused or read as a short name for England (this character is the first syllable of the word for England, the English language, the British Pound, and other titles from the British Isles).

In some contexts, this can mean “outstanding” or even “flower.” But it will most often read as having something to do with the United Kingdom.

This is not the most common way to say hero, courage or bravery but you may see it used sometimes.

I strongly recommend that you choose another form of courage/bravery.

This in-stock artwork might be what you are looking for, and ships right away...

Gallery Price: $79.00

Your Price: $43.88

Gallery Price: $65.00

Your Price: $39.88

Gallery Price: $158.00

Your Price: $87.77

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

Gallery Price: $100.00

Your Price: $49.88

Gallery Price: $65.00

Your Price: $39.88

Gallery Price: $72.00

Your Price: $39.88

Gallery Price: $87.00

Your Price: $47.88

Gallery Price: $108.00

Your Price: $59.88

The following table may be helpful for those studying Chinese or Japanese...

| Title | Characters | Romaji (Romanized Japanese) | Various forms of Romanized Chinese | |

| Change | 改變 / 改変 改变 | kaihen | gǎi biàn / gai3 bian4 / gai bian / gaibian | kai pien / kaipien |

| Bravery Courage | 勇 | isamu / yu- | yǒng / yong3 / yong | yung |

| Bravery Courage | 勇氣 勇气 / 勇気 | yuuki / yuki | yǒng qì / yong3 qi4 / yong qi / yongqi | yung ch`i / yungchi / yung chi |

| Wind of Change | 風雲變幻 风云变幻 | fēng yún biàn huàn feng1 yun2 bian4 huan4 feng yun bian huan fengyunbianhuan | feng yün pien huan fengyünpienhuan |

|

| Move On Change Way of Thinking | 乗り換える | norikaeru | ||

| Courage and Strength | 勇力 | yuu ri / yuuri / yu ri | yǒng lì / yong3 li4 / yong li / yongli | yung li / yungli |

| Courage to do what is right | 見義勇為 见义勇为 | jiàn yì yǒng wéi jian4 yi4 yong3 wei2 jian yi yong wei jianyiyongwei | chien i yung wei chieniyungwei |

|

| Inspire with redoubled courage | 勇気百倍 | yuuki hyaku bai yuukihyakubai yuki hyaku bai | ||

| Strength and Courage | 力量和勇氣 力量和勇气 | lì liàng hé yǒng qì li4 liang4 he2 yong3 qi4 li liang he yong qi liliangheyongqi | li liang ho yung ch`i lilianghoyungchi li liang ho yung chi |

|

| Bravery Courage | 勇敢 | yuu kan / yuukan / yu kan | yǒng gǎn / yong3 gan3 / yong gan / yonggan | yung kan / yungkan |

| Honor Courage | 尊嚴勇氣 尊严勇气 | zūn yán yǒng qì zun1 yan2 yong3 qi4 zun yan yong qi zunyanyongqi | tsun yen yung ch`i tsunyenyungchi tsun yen yung chi |

|

| Courage To Do What Is Right | 義を見てせざるは勇なきなり | giomitesezaruhayuunakinari giomitesezaruhayunakinari | ||

| Serenity Prayer | 上帝賜給我平靜去接受我所不能改變的給我勇氣去改變我所能改變的並給我智慧去分辨這兩者 上帝赐给我平静去接受我所不能改变的给我勇气去改变我所能改变的并给我智慧去分辨这两者 | shàng dì cì wǒ píng jìng qù jiē shòu wǒ suǒ bù néng gǎi biàn de wǒ yǒng qì qù gǎi biàn wǒ suǒ néng gǎi biàn de bìng wǒ zhì huì qù fēn biàn zhè liǎng zhě shang4 di4 ci4 gei3 wo3 ping2 jing4 qu4 jie1 shou4 wo3 suo3 bu4 neng2 gai3 bian4 de gei3 wo3 yong3 qi4 qu4 gai3 bian4 wo3 suo3 neng2 gai3 bian4 de bing4 gei3 wo3 zhi4 hui4 qu4 fen1 bian4 zhe4 liang3 zhe3 shang di ci gei wo ping jing qu jie shou wo suo bu neng gai bian de gei wo yong qi qu gai bian wo suo neng gai bian de bing gei wo zhi hui qu fen bian zhe liang zhe | shang ti tz`u kei wo p`ing ching ch`ü chieh shou wo so pu neng kai pien te kei wo yung ch`i ch`ü kai pien wo so neng kai pien te ping kei wo chih hui ch`ü fen pien che liang che shang ti tzu kei wo ping ching chü chieh shou wo so pu neng kai pien te kei wo yung chi chü kai pien wo so neng kai pien te ping kei wo chih hui chü fen pien che liang che |

|

| Strength and Courage | 力と勇氣 力と勇気 | riki to yu ki rikitoyuki | ||

| Serenity Prayer | 神様は私に変える事の出来ない物を受け入れる穏やかさと変える事の出来る勇気とその違いを知る賢明さを与える | kamisama ha watashi ni kaeru koto no deki nai mono o ukeireru odayaka sa to kaeru koto no dekiru yuuki to sono chigai o shiru kenmei sa o ataeru kamisama ha watashi ni kaeru koto no deki nai mono o ukeireru odayaka sa to kaeru koto no dekiru yuki to sono chigai o shiru kenmei sa o ataeru | ||

| Honor Courage Commitment | 名譽, 勇気, 決意 名誉, 勇気, 決意 | meiyo yuuki ketsui meiyoyuukiketsui meiyo yuki ketsui | ||

| Honor Courage Commitment | 榮譽勇氣責任 荣誉勇气责任 | róng yù yǒng qì zé rèn rong2 yu4 yong3 qi4 ze2 ren4 rong yu yong qi ze ren rongyuyongqizeren | jung yü yung ch`i tse jen jungyüyungchitsejen jung yü yung chi tse jen |

|

| Fidelity Honor Courage | 信義尊嚴勇氣 信义尊严勇气 | xìn yì zūn yán yǒng qì xin4 yi4 zun1 yan2 yong3 qi4 xin yi zun yan yong qi xinyizunyanyongqi | hsin i tsun yen yung ch`i hsinitsunyenyungchi hsin i tsun yen yung chi |

|

| Brave the Waves | 破浪 | ha rou / harou / ha ro | pò làng / po4 lang4 / po lang / polang | p`o lang / polang / po lang |

| Advance Bravely Indomitable Spirit | 勇往直前 | yǒng wǎng zhí qián yong3 wang3 zhi2 qian2 yong wang zhi qian yongwangzhiqian | yung wang chih ch`ien yungwangchihchien yung wang chih chien |

|

| Fortune favors the brave | 勇者は幸運に恵まれる | yuusha ha kouun ni megumareru yusha ha koun ni megumareru | ||

| Learning leads to Knowledge, Study leads to Benevolence, Shame leads to Courage | 好學近乎知力行近乎仁知恥近乎勇 好学近乎知力行近乎仁知耻近乎勇 | hào xué jìn hū zhī lì xíng jìn hū rén zhī chǐ jìn hū yǒng hao4 xue2 jin4 hu1 zhi1 li4 xing2 jin4 hu1 ren2 zhi1 chi3 jin4 hu1 yong3 hao xue jin hu zhi li xing jin hu ren zhi chi jin hu yong | hao hsüeh chin hu chih li hsing chin hu jen chih ch`ih chin hu yung hao hsüeh chin hu chih li hsing chin hu jen chih chih chin hu yung |

|

| No Fear | 恐れず | oso re zu / osorezu | ||

| No Fear | 無畏 无畏 | mui | wú wèi / wu2 wei4 / wu wei / wuwei | |

| A Wise Man Changes His Mind (but a fool never will) | 君子豹変す | kun shi hyou hen su kunshihyouhensu kun shi hyo hen su | ||

| No Guts, No Glory | 無勇不榮 无勇不荣 | wú yǒng bù róng wu2 yong3 bu4 rong2 wu yong bu rong wuyongburong | wu yung pu jung wuyungpujung |

|

| Mark the boat to find the lost sword Ignoring the changing circumstances of the world | 刻舟求劍 刻舟求剑 | kokushuukyuuken kokushukyuken | kè zhōu qiú jiàn ke4 zhou1 qiu2 jian4 ke zhou qiu jian kezhouqiujian | k`o chou ch`iu chien kochouchiuchien ko chou chiu chien |

| Progress Day by Day | 日漸 日渐 | rì jiàn / ri4 jian4 / ri jian / rijian | jih chien / jihchien | |

| Zhong Kui | 鐘馗 钟馗 | zhōng kuí zhong1 kui2 zhong kui zhongkui | chung k`uei chungkuei chung kuei |

|

| Evolve Evolution | 演化 | yǎn huà / yan3 hua4 / yan hua / yanhua | yen hua / yenhua | |

| Sitting Quietly | 靜坐 静坐 | sei za / seiza | jìng zuò / jing4 zuo4 / jing zuo / jingzuo | ching tso / chingtso |

| Flexibility | 靈活性 灵活性 | líng huó xìng ling2 huo2 xing4 ling huo xing linghuoxing | ling huo hsing linghuohsing |

|

| Shapeshifter | 變形者 变形者 | biàn xíng zhě bian4 xing2 zhe3 bian xing zhe bianxingzhe | pien hsing che pienhsingche |

|

| Innovation | 革新 | kakushin | gé xīn / ge2 xin1 / ge xin / gexin | ko hsin / kohsin |

| Engage with Confidence | 理直氣壯 理直气壮 | lǐ zhí qì zhuàng li3 zhi2 qi4 zhuang4 li zhi qi zhuang lizhiqizhuang | li chih ch`i chuang lichihchichuang li chih chi chuang |

|

| No Surrender | 義無反顧 义无反顾 | yì wú fǎn gù yi4 wu2 fan3 gu4 yi wu fan gu yiwufangu | i wu fan ku iwufanku |

|

| Dynamic | 動 动 | dou / do | dòng / dong4 / dong | tung |

| Justice Righteousness | 正義 正义 | sei gi / seigi | zhèng yì / zheng4 yi4 / zheng yi / zhengyi | cheng i / chengi |

| Joshua 1:9 | 我豈沒有吩咐你嗎你當剛強壯膽不要懼怕也不要驚惶因為你無論往哪里去耶和華你的神必與你同在 我岂没有吩咐你吗你当刚强壮胆不要惧怕也不要惊惶因为你无论往哪里去耶和华你的神必与你同在 | wǒ qǐ méi yǒu fēn fù nǐ ma nǐ dāng gāng qiáng zhuàng dǎn bù yào jù pà yě bù yào jīng huáng yīn wèi nǐ wú lùn wǎng nǎ lǐ qù yē hé huá nǐ de shén bì yǔ nǐ tóng zài wo3 qi3 mei2 you3 fen1 fu4 ni3 ma ni3 dang1 gang1 qiang2 zhuang4 dan3 bu4 yao4 ju4 pa4 ye3 bu4 yao4 jing1 huang2 yin1 wei4 ni3 wu2 lun4 wang3 na3 li3 qu4 ye1 he2 hua2 ni3 de shen2 bi4 yu3 ni3 tong2 zai4 wo qi mei you fen fu ni ma ni dang gang qiang zhuang dan bu yao ju pa ye bu yao jing huang yin wei ni wu lun wang na li qu ye he hua ni de shen bi yu ni tong zai | wo ch`i mei yu fen fu ni ma ni tang kang ch`iang chuang tan pu yao chü p`a yeh pu yao ching huang yin wei ni wu lun wang na li ch`ü yeh ho hua ni te shen pi yü ni t`ung tsai wo chi mei yu fen fu ni ma ni tang kang chiang chuang tan pu yao chü pa yeh pu yao ching huang yin wei ni wu lun wang na li chü yeh ho hua ni te shen pi yü ni tung tsai |

|

| Trust No One Trust No Man | 誰も信じるな | dare mo shin ji ru na daremoshinjiruna | ||

| Lover Spouse Sweetheart | 愛人 爱人 | ai jin / aijin | ài ren / ai4 ren / ai ren / airen | ai jen / aijen |

| Mujo no Kaze Wind of Impermanence | 無常の風 | mu jou no kaze mujounokaze mu jo no kaze | ||

| Bushido The Way of the Samurai | 武士道 | bu shi do / bushido | wǔ shì dào wu3 shi4 dao4 wu shi dao wushidao | wu shih tao wushihtao |

| Prosperity | 繁栄 繁荣 | hanei | fán róng / fan2 rong2 / fan rong / fanrong | fan jung / fanjung |

| Kai Zen Kaizen | 改善 | kai zen / kaizen | gǎi shàn / gai3 shan4 / gai shan / gaishan | kai shan / kaishan |

| Immovable Mind | 不動心 | fu dou shin fudoushin fu do shin | ||

| Glory and Honor | 榮 荣 / 栄 | ei | róng / rong2 / rong | jung |

| Islam | 伊斯蘭教 伊斯兰教 | yī sī lán jiào yi1 si1 lan2 jiao4 yi si lan jiao yisilanjiao | i ssu lan chiao issulanchiao |

|

| Dana: Almsgiving and Generosity | 布施 | fuse | bù shī / bu4 shi1 / bu shi / bushi | pu shih / pushih |

| Life Energy Spiritual Energy | 氣 气 / 気 | ki | qì / qi4 / qi | ch`i / chi |

| Better Late Than Never | 亡羊補牢猶未為晚 亡羊补牢犹未为晚 | wáng yáng bǔ láo yóu wèi wéi wǎn wang2 yang2 bu3 lao2 you2 wei4 wei2 wan3 wang yang bu lao you wei wei wan | wang yang pu lao yu wei wei wan wangyangpulaoyuweiweiwan |

|

| England | 英 | ei | yīng / ying1 / ying | |

| In some entries above you will see that characters have different versions above and below a line. In these cases, the characters above the line are Traditional Chinese, while the ones below are Simplified Chinese. | ||||

Successful Chinese Character and Japanese Kanji calligraphy searches within the last few hours...